10 Reasons why Margaret Thatcher is Britain's most hated politician

Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990, is one of the most divisive figures in British Political history.

Ever wondered why she is so hated by some and loved by others?

Unquestionably strong and successful in her political career, she has garnered love and hate in near equal measure, though some say she merely highlighted the divisions already present in society at the time.

Thatcher – Why is she hated?

I can’t hope to cover all of the reasons people hate Thatcher. I couldn't even hope to cover all the reasons why people don't hate her, and there are seemingly considerably fewer of those!

What I can do though is highlight some of the main reasons why Thatcher was hated, so below I've selected the ten main reasons most often cited. These 10 reasons go a long way to explaining the strength of feeling her legacy has left.

Jump to a reason…

Looking for a specific reason why people hate Thatcher? Click on a link below to jump directly to the relevant section…

- She supported the retention of Capital Punishment

- She destroyed Britain’s manufacturing industry and her policies led to mass unemployment

- She presided over interest rates of 15%

- She voted against the relaxation of divorce laws

- She abolished free milk for School Children

- She precipitated a Social Housing crisis still being felt today

- The Poll Tax

- She sowed the seeds of NHS Privatisation

- Section 28 – Thatchers quiet homophobia?

- The Irish Hunger Strikes

For a list of further reason, check out this post by Mike Harding on Facebook.

1. She supported the retention of Capital Punishment

Well, she did. As a personal view, but not one she imposed on the party, as she expressed in an interview with Channel Four in October 1985.

Paul Jones “Thank you very much. Prime Minister, we have had a lot of questions on a variety of subjects, with obviously a great many of them on the bomb outrage at Brighton.

There is a question here which says: Will the Conservatives now be backing a law to restore the death penalty in the light of what happened in Brighton?”

Prime Minister “I expect that there will be a demand to have another debate on the death penalty. We had one at the beginning of this Parliament. I personally have always voted for the death penalty because I believe that people who go out prepared to take the lives of other people forfeit their own right to live.

I believe that that death penalty should be used only very rarely, but I believe that no-one should go out certain that no matter how cruel, how vicious, how hideous their murder, they themselves will not suffer the death penalty.

But I say that as a personal view. There has never been a party political view on the death penalty. It has always been held that we vote individually.

I have consistently voted to retain the death penalty for the reasons which I have given.”

2. She destroyed Britain’s manufacturing industry and her policies led to mass unemployment

Thatcher’s policies were not directed at causing mass unemployment but that was a consequence of her policies designed to control inflation, which at one point hit 18%.

Her Deflationary Strategy included several measures such as increasing interest rates and raising VAT from 8% to 15%.

These measures, coupled with the receipts from North Sea oil lead to a strengthening of Pound Sterling and hit export manufacturing incredibly hard.

Despite public outcry and plunging popularity, Thatcher stood firm in her policies, leading to one of her most famous quotes:

“To those waiting with bated breath for that favourite media catch-phrase—the U-turn—I have only one thing to say: you turn if you want to; the Lady’s not for turning.”

Ultimately her policies and the link between money supply and inflation were proven correct and inflation lowered to 8.5% by 1982.

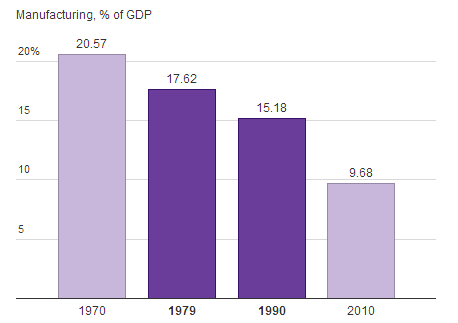

But that was not before over 2 million manufacturing jobs had been lost in the 1979-81 recession and swathes of industry had been decimated, never to recover - though Tony Blair's Labour administration actually contributed more to manufacturing decline, as seen in the GDP graphic below.

After the recession in 1983, manufacturing output was 30% lower than 1978 levels, reducing the manufacturing base so much that the balance of payments in manufactured goods was in deficit - and has been there ever since.

HOWEVER – Finding a definitive resolution on the question of Britain’s manufacturing, Thatcher’s role in it’s demise and the extent to which it was about to implode under the weight of the Unions is virtually impossible.

It’s true to say that Britian was in dire straights in the 1970′s, dubbed the ‘Sick Man of Europe‘, it struggled with rising unemployment (up from around 500,000 to 1,500,000 since the start of the 70′s) and repeated strikes, culminating in the failed Social Contract and the Winter of Discontent.

To say she took measures to deregulate the banks and promote a Free Market economy based on the Service industry also can’t be disputed, it’s exactly the economy the UK has now and is a direct result of her actions.

What is less welcome to many people is that Britain was in critical need of this change. Andrew Sullivan sums it up well in his piece, Thatcher, Liberator:

“You can read elsewhere the weighing of her legacy – but she definitively ended a truly poisonous, envious, inert period in Britain’s history. She divided the country deeply – and still does.

She divided her opponents even more deeply, which was how she kept winning elections.

She made some serious mistakes – the poll tax, opposition to German unification, insisting that Nelson Mandela was a terrorist – but few doubt she altered her country permanently, re-establishing the core basics of a free society and a free economy that Britain had intellectually bequeathed to the world and yet somehow lost in its own class-ridden, envy-choked socialist detour to immiseration.”

She unquestionably stirs up hatred for her actions during this time, it’s up to you to decide whether, on balance, she was right to take them.

For a more 'thorough' review you can read a detailed analysis from the Centre for Business Research on the History of British Industrial Performance from 1870-2010, or The impact of Government policies on UK manufacturing since 1945.

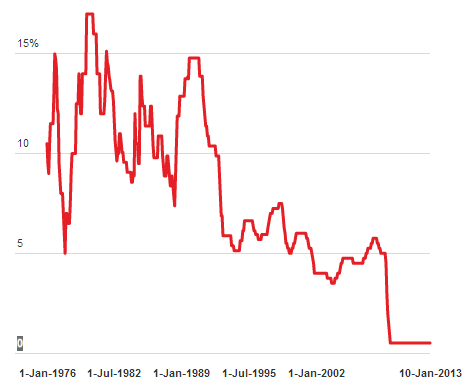

3. She presided over interest rates of 15%

She did. This Guardian article and the linked Google Spreadsheet has a number for excellent interactive charts where you can plot various economic indicators over the course of the Thatcher Government and beyond.

More important than simply being in office during the time of such rates were the consequences and the measures taken to control them.

This Parliamentary Briefing Paper shows one of the biggest - repossessions.

Source: The Guardian

Ordinary home owners, many of whom had bought their homes as a direct result of the Right to Buy scheme, found themselves losing their homes due to spiraling mortgage payments. However, it must be said that the bulk of repossessions happened directly after Thatcher left office, though no doubt many rightly attribute their defaults to the period of high interest rates that preceded her departure.

Though the control of inflation was ultimately achieved, this further damage to ordinary people, millions of whom had already lost their jobs thanks to the impact on manufacturing, lead to a deep rooted personal hatred of Thatcher and Thatcherism.

4. She voted against the relaxation of divorce laws

She did, but the Bill passed anyway. Prior to The Divorce Reform Act 1969, it was impossible for a “guilty” party to divorce and an innocent party.

As long as the innocent spouse took care not to be caught in adultery, he or she could effectively block the other’s divorce and remarriage.

5. She abolished free milk for School Children

As ever, things are more complicated. In the 70′s there was significant pressure in the Wilson Government to make spending cuts in order to pay for Tax savings.

Thatcher, the new Secretary of State for Education at the time, was ordered to make cuts in four areas:

- Further Education fees

- Library book borrowing charges

- School meal charges

- Free school milk

Concerned over the effect of the cuts to milk, she said:

“I think that the complete withdrawal of free milk for our school children would be too drastic a step and would arouse more widespread public antagonism than the saving justifies.”

She proposed a compromise, that would later be accepted, to remove milk provision for those aged 7 to 11 but retain it for primary school pupils for nutritional purposes. Despite this, she was still labelled “Margaret Thatcher, Milk Snatcher“.

It should also be noted that this wasn’t the first time milk provision had been removed from school children. In 1968, the then Labour Education Secretary Edward Short removed free milk from secondary schools, 3 years before Thatcher continued the phased removal for primary school pupils over 7.

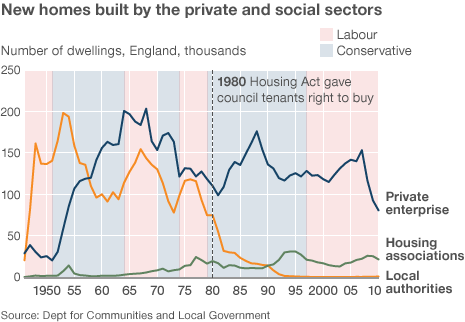

6. She precipitated a Social Housing crisis still being felt today

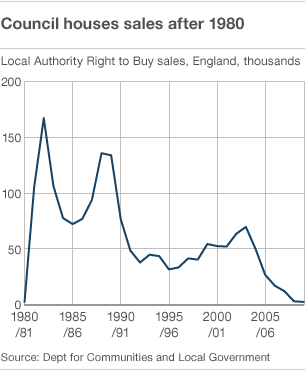

She did. There can’t be much argument that her massive expansion and subsidisation of the Right to Buy scheme saw Council House purchases soar from around 50,000 in 1972 to nearly 200,00 in 1982.

These graphics from the BBC highlight the changes:

It’s been more than 20 years since she left power, including a 13 year Labour Government. It is therefore prudent to ask at what point responsibility for the current situation switches to successive Governments who have failed to correct this imbalance.

However, there is little doubt that the sweeping changes and current social problems blighting many areas that the Right to Buy brought had their origins in the Thatcher Government*.

* Even if those consequences may not have been intended to go as deep as they did, what with Thatcher’s belief in the Free Market and Private Enterprise stepping in to fill the gap left by Privatisation.

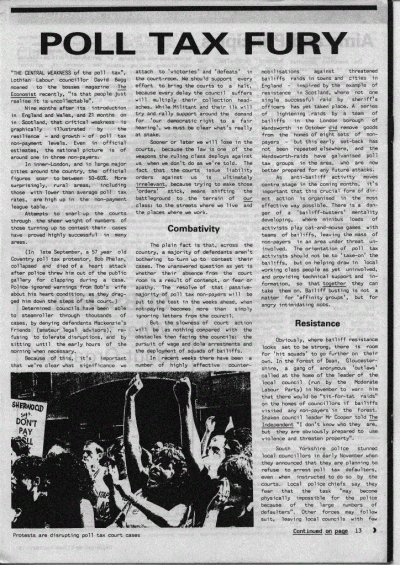

7. The Poll Tax

The Poll Tax is the stand-out, unequivocal disaster of the Thatcher Government. Also known as the ‘Community Charge‘, this ill-conceived legislation led directly to the downfall of Thatcher.

It’s even been suggested that had voter registration not been so low as people tried to avoid being identified to pay the charge, it’s likely that the Conservatives would have been removed from power during the 1992 general election. Though, that's a somewhat contested claim.

Many believed that changing the way the tax was calculated, from the estimated market value of a property to the number of people living in it, was a backwards step.

It was a backwards step.

It moved the burden of tax from the rich to the poor.

It disproportionately hit large families living in relatively small accommodation and was universally hated for being unfair on ordinary working people.

The Community Charge caused intense distrust and deep wounds in the political psyche of millions of voters, many of whom never forgave Thatcher for her actions (as we see from the anger released following her death).

The changes generated seething public anger, mass protests, public disobedience, mass refusal to pay, legal challenges and some of the worst rioting ever seen in England.

Yorkshire Police even made preparations to refuse to arrest anyone as thanks to the problems of implementing the tax, the force believed it lacked the resources to deal with such wide-scale civil disobedience.

A note on the Consequences

As a direct result of the catastrophe befalling the Conservative Party and the upturn in support for Labour, many Conservative MP’s wanted to get rid of the Poll Tax but thought they couldn’t with Thatcher still in power.

Following the resignation of Deputy Prime Minister Geoffrey Howe and subsequent leadership challenge by Michael Heseltine, Thatcher resigned in November 1990. John Major won the resultant leadership contest and immediately abolished the Community Charge.

He replaced it with 'Council Tax' in 1993 following the Local Government Finance Act 1992. It was based on the essentially identical Rates system used prior to the Community Charge.

Such is the strength of feeling still felt in Britain about the Community Charge, politicians have consistently steered clear of adjusting it for over 20 years, save for minor alterations aimed primarily at increasing discounts for certain households and individuals.

8. She sowed the seeds of NHS Privatisation

As ever, things are more subtle. Following recommendations in the Griffith’s Report the Thatcher government introduced ‘Modern Management Processes’ to replace the older system on ‘Consensus Management’. Then in 1988, and again in 1989, a review of the NHS (and subsequent White Papers ‘Working for Patients’ and ‘Caring for People’), led to the introduction in England of National Health Service & Community Care Act.

This Act defined what was to be known as the ‘Internal Market’, which introduced the following changes:

“The market splits health authorities (which commission care for their local population) from hospital trusts (which compete to provide care). GP fundholding, which gives some family doctors budgets to buy care on their patients’ behalf, is introduced.’

In The Impact of the NHS Market, CIVITAS described the intention was:

“...for purchasers to choose the most suitable services at the best prices. Healthcare services could be purchased from public (NHS) providers (including new self-governing hospitals called NHS Trusts, other health authorities’ hospitals, and health authorities’ own self-managed hospitals) and independent suppliers, who were all to compete for contracts.” “Fundholders were to be motivated by the ability to reinvest any profit gained from efficient purchasing back into general practice, to spend as they liked.”

CIVITAS goes on to say:

The Labour Party initially campaigned against the internal market, claiming it had fragmented the NHS and distorted incentives. Upon coming to power in 1997, they published The New NHS: modern, dependable, which rejected both the old command-and-control management of the 1970s and 80s, and the Conservatives’ internal market. However, the purchaser-provider split was retained and carried on through a new ‘third way’.

In theory this policy aim endorsed a public/private ‘partnership’ approach to running the NHS, but in practice it created an intense focus on performance measurement (targets and monitoring). GP fundholding was abolished, and primary care groups (later primary care trusts) were established as the new commissioning bodies, but with a greater focus on needs assessment and accountability to the local community. District health authorities became, simply, health authorities (and later ‘strategic health authorities’).

Although they initially helped primary care groups with needs assessment, they were to ultimately take on a more managerial role, determining local targets and standards.

Even if Thatcher’s Government did introduce such reforms, others have certainly expanded on them, even the aforementioned Labour administration under Tony Blair.

If she can be held responsible for getting the ball rolling, it’s questionable as to whether she can be held accountable for the current state of the NHS or for the failure of successive administrations to corrects the ills of her reforms.

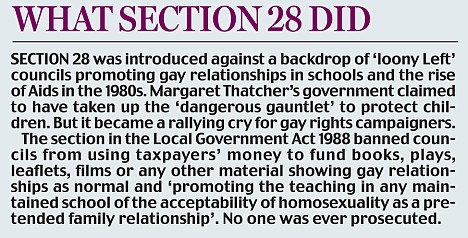

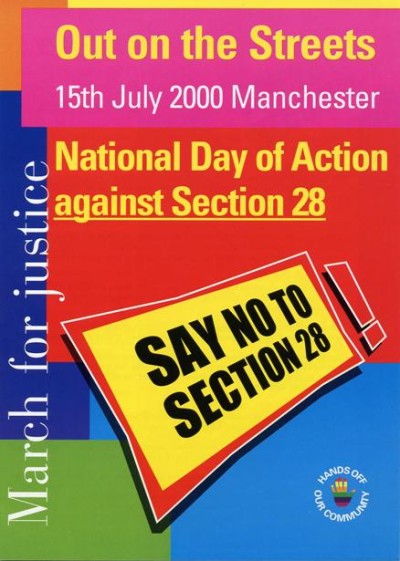

9. Section 28 – Thatchers quiet homophobia?

This is one of the apparently obvious, but in reality, confused reasons why people ‘hate’ Thatcher herself. The sentiment is more rightly directed at the Conservative Party as a whole. Section 28 refers to Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 which stated:

A local authority shall not–

(a) intentionally promote homosexuality or publish material with the intention of promoting homosexuality;

(b) promote the teaching in any maintained school of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.

There is little evidence to say that Thatcher was directly involved in the Act’s creation, (it was Jill Knight who introduced the specific Section itself) and indeed far more to suggest that modern politicians such as William Hague actively supported the clause.

Nonetheless, such legislation reflects the generally held beliefs of the Conservative traditionalists that Homosexuality, though no longer illegal, should not be promoted.

Modernists, including current Prime Minister David Cameron, no longer support such sentiment. Cameron even went so far as to issue a much needed and long overdue apology in July 2009, despite he himself having voted for a retention of the Section in 2003. He stated:

“Yes, we may have sometimes been slow and, yes, we may have made mistakes, including Section 28, but the change has happened.”

This highly complex topic developed over months and you should take the time to read the background, particularly the testimony of Jill Knight (excerpt below), who introduced Section 28:

“This all happened after pressure from the Gay Liberation Front. At that time I took the trouble to refer to their manifesto, which clearly stated: “We fight for something more than reform. We must aim for the abolition of the family…”

Regardless, the legislation was later confirmed as being inapplicable to Schools, and didn’t prohibit the objective discussion of sexuality, or prohibit any discussion related to the prevention of the disease.

What it did do was serve to highlight and ostracise the Gay and Lesbian community, legislating for separate treatment and restriction of teaching that many LGBT supports legitimately felt discriminated against them.

It perpetuated a feeling of resentment and distrust of the LGBT community, serving as a clear example of homophobia and prejudice within the institution of Government. The feeling of vilification felt by many in the Gay Community can therefore, understandably, explain their dislike of Thatcher and her government.

In modern Britain, the Section, and it’s relatively recent repeal, sits as an awkward revelation of the Conservative parties deep rooted traditionalism and fear over homosexuality, which continues today with the issue of Gay Marriage.

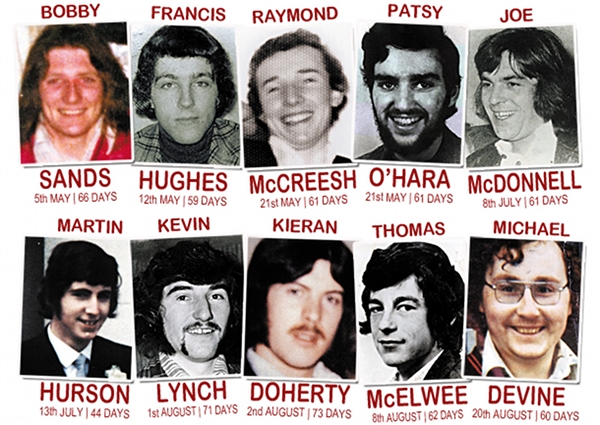

10. The Irish Hunger Strikes

The Irish Hunger Strike in 1981 were an extraordinary development in the history of the Northern Ireland troubles and set the tone for decades to come.

It was the culmination of 5 years of protests by Irish Republican prisoners, having begun in 1976 after Britain removed Special Category Status (essentially ‘Political Prisoner’ status) for captured paramilitary prisoners.

The Blanket Men’s primary aim was to reinstate their categorisation as essentially ‘Prisoner’s of War’ and the attached privileges awarded under that status. Specifically their goals included:

- The right not to wear a prison uniform;

- The right not to do prison work;

- The right of free association with other prisoners, and to organise educational and recreational pursuits;

- The right to one visit, one letter and one parcel per week;

- Full restoration of remission lost through the protest.

A complex timeline of events ultimately led to the the deaths of 10 prisoners. But that was not before an incredible development – the leader of the Hunger Strike, and one of those who would later go on to die, Bobby Sands was elected, from his prison cell, to the British House of Commons following a By-Election in 1981.

Sands election led to a media frenzy and even a visits from an envoy to Pope John Paul II and The European Commission on Human Rights with the intention of resolving the situation.

But hopes that the situation could be resolved diminished with Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Humphrey Atkins stating:

“If Mr. Sands persisted in his wish to commit suicide, that was his choice. The Government would not force medical treatment upon him”

Thatcher also solidified her stance, saying:

“We are not prepared to consider special category status for certain groups of people serving sentences for crime. Crime is crime is crime, it is not political”

Following Sands death, 100,000 people attended his funeral and such was the international feeling over the situation, the cities of Paris and Tehran even named streets in Sands honour. Throughout the crisis, Thatcher remain absolutely resolute in the face of extraordinary national and international political and moral pressure.

Bobby Sands MP Mural – Northern Ireland

Her tone in May 1981 was at times morbid, even as the Hunger Strikers began to die one after another:

“Faced with the failure of their discredited cause, the men of violence have chosen in recent months to play what may well be their last card.”

Following Sands death she coolly stated to the House of Commons:

“Mr. Sands was a convicted criminal. He chose to take his own life. It was a choice that his organisation did not allow to many of its victims”

As the months passed, the Hunger Strike began to break when the families of various strikers authorised medical intervention and forced feeding should the men become unconscious.

Within 3 days of the strike’s end on October 3rd 1981, new Secretary of State for Northern Ireland James Prior announced partial concessions to the prisoners including the right to wear their own clothes at all times.

Following subsequent sabotage and the Maze Prison Escape in 1983, the prison workshops were closed, effectively reinstating the Strikers final demand ‘not to do prison work’.

Though many in the British press lauded Thatcher and her ‘success’ in standing resolute against the Hunger Strikers, in reality the victory was a hollow one. Thatcher became a hate figure of unrivalled stature within sections of Northern Ireland and even the British and International public. Her handling of the crisis drew international condemnation.

Thatcher’s actions directly led to a straining of the relationship between the British and Irish Government and a marked upturn in violence following the comparatively quiet period of the late 1970′s.

Republican writer Danny Morrison’s now famous quote has come to symbolise the sentiment of the time, describing Thatcher as:

”…the biggest bastard we have ever known”

In 1984, several years after the Hunger Strikes, the resentment went beyond mere feeling as the IRA launched a very nearly successful assassination attempt on Thatcher on the night before the Conservative Party Conference.

Several floors collapsed and 5 people were killed

5 people died in the Brighton Hotel Bombing and Thatcher herself only narrowly avoided being killed.

Public feeling in Britain shifted following the bombing, with many personally supporting Thatcher and her decision to stand at on the stage at 9am the same day ready to deliver her party speech.

She remain resolute, stating:

“This attack has failed. All attempts to destroy democracy by terrorism will fail.”

Why is Margaret Thatcher Hated?

Hindsight is always 20:20, and we must remember that when judging the dead. Actions taken during a crisis, political, economic or even conflict, are taken based on the information available at the time.

During war, leaders must take decisions that can lead to people losing their lives. Similarly, during an economic crisis leaders must take decision that can lead to people being made unemployed or losing their homes. The key point here is that leaders must make decisions.

Judging those decisions is, for the most part, subjective and depends on whether you lost or gained as a result. Can Thatcher and the Conservatives expect to retain support in the devastated manufacturing heartlands of our proud country?

No, they can’t.

The destruction of community and way of life was total. So much so that a subsequent 13 year Labour Government couldn’t even begin to countenance introducing policies that would have promoted a return to the historic economic and social structure of these areas.

Likewise, can Thatcher and the Conservatives expect support from the millions of home owning, share holding, middle class Britons sweeping the southern Shires? How about the high rolling city institutions or financial powerhouses that fuel our modern economy? Or the enterprising entrepreneurs, the ‘sole traders’ of the Del Boy generation?

Yes, they can.

That is the real reason why Thatcher is divisive – some people lost and some people gained. There was no middle ground. There was almost no sense of ‘degree’. Her utter determination of will and her imposition of her ideals on the British socio-economic fabric has been total.

And people were burned during the transition.

For many, the damage runs so deep that the wounds will never heal. This is a story of ideologies and seldom in such tales are enemies reconciled.